|

|

You go because it’s a long step from ordinary. You go because you read tales by Andy Russel and his book “Horns in the High Country”. You’ve carried on your back the stuff needed to survive two weeks in some remote wild valley. You’ve taken saddle and pack horses into country few people have seen. From a mountaintop, you’ve viewed a sea of peaks where the only sound you’ve heard is the wind or the occasional raven call.

Now in mid-winter, it’s time to start inspecting gear for next sheep season. Backpack and survival gear cover the den floor. Sporting goods stores are visited and the latest gear is inspected. Seems like something better is always available. This could become an expensive activity—new rifles, boots, pack tent, sleeping bag, breathable waterproof clothing—the possibilities are endless.

Sheep season really starts about mid-August. Fly rod, binoculars and spotting scope in the saddlebags and you’re equipped. A small camera with a good zoom and some of the best “wild” encounters can be captured.

Last summer the encounters were of the grizzly kind. Five in one day—I really wonder why they are considered endangered.

|

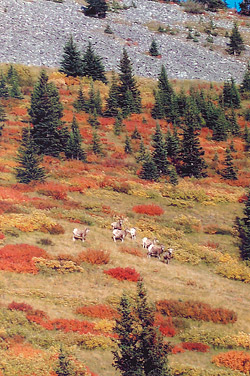

| Band of rams feeding on a colourful fall slope. |

August 23rd and I’ve set up a cozy camp on a ridge with a good view of open slopes where I’ve been seeing a group of rams all summer. Several times a fine mature ram has visited this group but never lingered long. The week passes with beautiful fall weather; the band of young rams seems to have learned to accept my presence. Finally, one early morning, I emerge from my tent and look to the opposing slope to see my band of neighbours. Movement at the skyline above them draws my attention to the large ram and a younger companion passing over the top and out of sight. Time to move on.

A couple of weeks later and I’m back. Later means cooler weather and often the snow in sheep country makes hunting practically impossible. This year my favourite range is still accessible. The slope across from camp is dotted with bodies of sheep on a snowy slope.

There in plain view are ewes and lambs. Then movement below them reveals a band of 12 rams. At least two of them have the older heavily broomed horns that true sheep admirers crave. It’s too late to start a stalk, so I’ll have to hope they’re still there in the morning.

Sleep is fitful, the night endless. It’s still dark when I rise to begin getting ready for a day on the mountain. Unfortunately, heavy snowflakes are descending. The slopes are covered by a white shroud—I’ll have to wait it out. By 10:00 a.m. there’s a break in the storm. Glassing the slopes where the sheep were the previous night reveals a white blanket of snow without even the hint of a track where the animals had been. With the way the snow was piling up, it was time to head out. Waiting for a melt might mean waiting until April.

I haul my camp back out of the snowed-in high country. The snow depth lessens, when I reach the trailhead the sun is shining and the ground is barely dampened. There’s a secret valley only a two-mile pack back through the forest where in the past I’ve run into sheep, including a few rams. With supplies to last a week, I shoulder my pack and head off. There’s time to reach my old camping spot, set up camp and even do a little hunting.

|

| Rod Hennig warming up by a small campfire. |

The spot feels so familiar. I know which trails to follow, which to avoid, where sheep like to travel, where they feed and where they frequently bed. It’s getting late. I look at the slope above camp, only some 200 metres away. A year ago, on a snowy evening six fine rams had been spotted there. It had been a little dark and with the falling snow, trying to study the details of their horns was not possible. I’d “put them to bed” on that occasion. Another sleepless night and morning brought heavy snow, a whiteout, an almost caved-in tent and a struggle to do the smart thing and get back to my truck. Survival became the issue of the moment.

That year the snowstorm dropped 120 centimetres and sheep season ended early. That has happened about a dozen times in my 40 some years of hunting sheep in Alberta’s eastern slopes. It also happened when guiding moose hunters in northeastern Alberta. Helicopter rescues had been required that time. Then there was a grizzly hunt when guiding in the Yukon Territory. Bush planes had pulled out my hunter and his trophy. The question had been whether or not he’d be able to return for me. A couple of hours later, thankfully, he did. That was followed by two weeks of foul weather when no one flew.

Anyway, this night, fair weather holds and a serenade of wolf howls and bugling elk reminds me of where I am. Soon morning arrives and with the new day the promise of hiking a dry wash while studying sheep behaviour pulls me toward another day of adventure, photography, and more memories.

As I continue to climb, none of the usual places show much sign of sheep. Maybe the sheep are elsewhere. This draw has come up empty before. Rounding another bend the decision is made to stop and have some lunch. Feeling a little down, lunch at least gives me something else to focus on. The day is a little dull and I haven’t even taken any photos.

The opposing slope at this location is quite heavily forested, except where a slide area is strewn with splintered trees, boulders, and a few small patches of brush trying to cling to the tortured landscape. There’s a light coloured rock off to the right.

Whoa! Where’d that come from? A shot of adrenalin brings binoculars to focus. That’s a sheep! Even better, it’s a half curl ram feeding there. Inspecting every stump, bump, boulder, shrub, log, and patch of brown, other sheep come into focus. All are ewes, lambs and young rams. Except the shadows of the forest reveal a shape that doesn’t belong. It’s the broomed full curl horn of a ram. Problem is it’s all that can be distinguished of its owner. The ram must be bedded because the horn doesn’t change position or location.

After several hours, the horn is suddenly gone. I begin to wonder if I’ve imagined it. But about one hundred metres up slope, the whole ram comes into view, broadside and about 250 metres away. Positioning my rifle over my pack, the crosshairs on my scope find the ram. Problem! Two young rams have moved up to flank him, each fully covering the vitals of his body. Another waiting game. Then in tandem, they enter the forest only steps away and they’re gone.

Moments later, a glimpse of sheep all traveling uphill with speed make me wonder what’s spooking them. Perhaps a predator has entered their domain. I recall the time a wolverine approached a slope covered with ewes and lambs. Catching scent of this enemy, they vacated the area. Twenty minutes later, I spotted them moving over the next mountain. Would have taken me three hours to get there. Like the group on this hunt, once again sheep escaped danger. I wonder if it was me they had just fled from.

A later hunt with fellow sheep nut and friend, Gary Halowchuk, near Cadomin revealed a magnificent ram on a high snow-covered slope. We’d plowed our way up here in thigh-deep snow. Now we sat by a campfire trying to warm up and dry some of our damp clothing. The ram was about 800 metres away but it was straight through that deep snow. Last day of the season and time was too limited to make an attempt.

Another sheep season had passed and once again, no new trophy ram mounts would decorate our den walls.

But it’s not really about killing a ram. It’s about the more abstract. The smell of horse sweat, creaking saddle leather, the squeal of a pika. The strain of the next step up a steep crumbling slope or huddling behind a boulder for shelter from the mountain winds. The golds, grays, and auburns of a September slope. Places where wolves howl, elk bugle, and your next guest may well be a prowling grizzly.

Oh, my friends and I have killed rams. We may even harvest another one or two. But a critical and very special time occurs in the lives of hunters who stay at it long enough. The harvest is no longer of primary importance. It’s the hunt, the experiences in our beautiful natural world that completes the life of the outdoorsman. It’s the memories that carry us to our next hunt and make each day a bit closer to next season. ■

For previous Reader Stories click here.

|

|

|

|